Something Good #111: Souvenirs

"She belongs to the mousepads and touring holographic experiences now."

Everywhere you go in Mexico City (or should I say, everywhere tourists go), you see Frida Kahlo. Her face stares at you from magnets and murals, t-shirts and tchotchkes. She has ascended into that rare pantheon of artists whose identities have been completely absorbed by mass commerce. Along with van Gogh, Dalí, Haring,1 and Klimt, she belongs to the mousepads and touring holographic experiences now.

I find it hard to look at work by this kind of artist. My eyes can’t find purchase on “The Starry Night” or “The Persistence of Memory;” like diner portraits of James Dean and Marilyn Monroe, whatever meaning or power they once possessed has been flattened by repetition. The artists themselves blur into various predefined identities: mad genius, feminist icon, incurable romantic. The more widely these artists’ works are reproduced and shared, the less meaning accrues to them.

This is such an accepted fact of life, the war on “selling out” so long settled (the artists lost), that I feel like a crank complaining about it.

It almost felt a little disingenuous to book tickets, several weeks out, to the very-much-in-demand Casa Azul, the sprawling mansion in Cayoacán where Kahlo was born and died, and which now hosts the Frida Kahlo Museum. Still, I did, dutifully (I wanted my daughter to see Kahlo’s work in person so she had at least a sense of it up close), and I didn’t regret it. It’s a very good museum, presenting a detailed, thoughtful cross-section of Kahlo’s life and artistic identity by showing the spaces in which she actually lived and worked.

Walking through Kahlo’s living spaces in a snake-like line of tourists, looking at her personal copy of Das Kapital under glass, there was something heartbreaking about the global marketing phenomenon centered on an artist who, until her early death, was a committed Marxist. I thought a lot about whether an artist’s work could survive commodification, or whether it was destined to curdle into kitsch.

Not something you feel about the avaricious Salvador “Avida Dollars” Dalí, or Andy Warhol, artists who willed themselves into becoming infinite wealth multipliers. But for an artist who left behind an unfinished painting originally titled "Peace on Earth so the Marxist Science may Save the Sick and Those Oppressed by Criminal Yankee Capitalism"… participating in the Kahlo industry, even just by observation, still makes me uneasy and alienates me even more from the work.

One of the most interesting exhibits in the house was a series of rooms dedicated to Kahlo’s clothing. Famously, she caused a sensation in America and Europe by showing up to events in glorious Tehuana dresses, but the exhibit also shows us the constricting and painful prosthetics and supports she wore underneath, legacies of a childhood bout with polio and a truly horrific trolley accident in which she was literally impaled.

One of Kahlo’s most repeated themes was physical pain, and seeing the works up close, seeing the wheelchair where she painted and the day bed where she rested in the afternoon, I began to disentangle the Kahlo of pop culture with the art itself. I’ve written before about how pop culture, and most art not depicting the crucifixion or martyrdom, almost entirely avoids the universal subject of pain. As I write this, I’m sitting at my desk with woozy, distracting nerve pain in my arm and neck, an aggravating daily fact of life, and there’s almost no art that speaks to this feeling.

So, to see the way Kahlo rendered that visible, in self-portraits where nails dig into her flesh, or the various constricting, almost medieval devices that made her life bearable, and to see those devices and garments in person, to see the bed where she used mirrors to paint while supine, this meant something to me. It made me realize that seeing art in person, up close, nose to the glass, is a way of pushing past that veil of woozy commercialization.

So strange how work that insists on making us think about pain, about our tortured relationship to our own bodies, has become so popularized. I wonder if those particles of meaning and pain make it into the souls of the people who buy the millions of mechanical reproductions of her work.

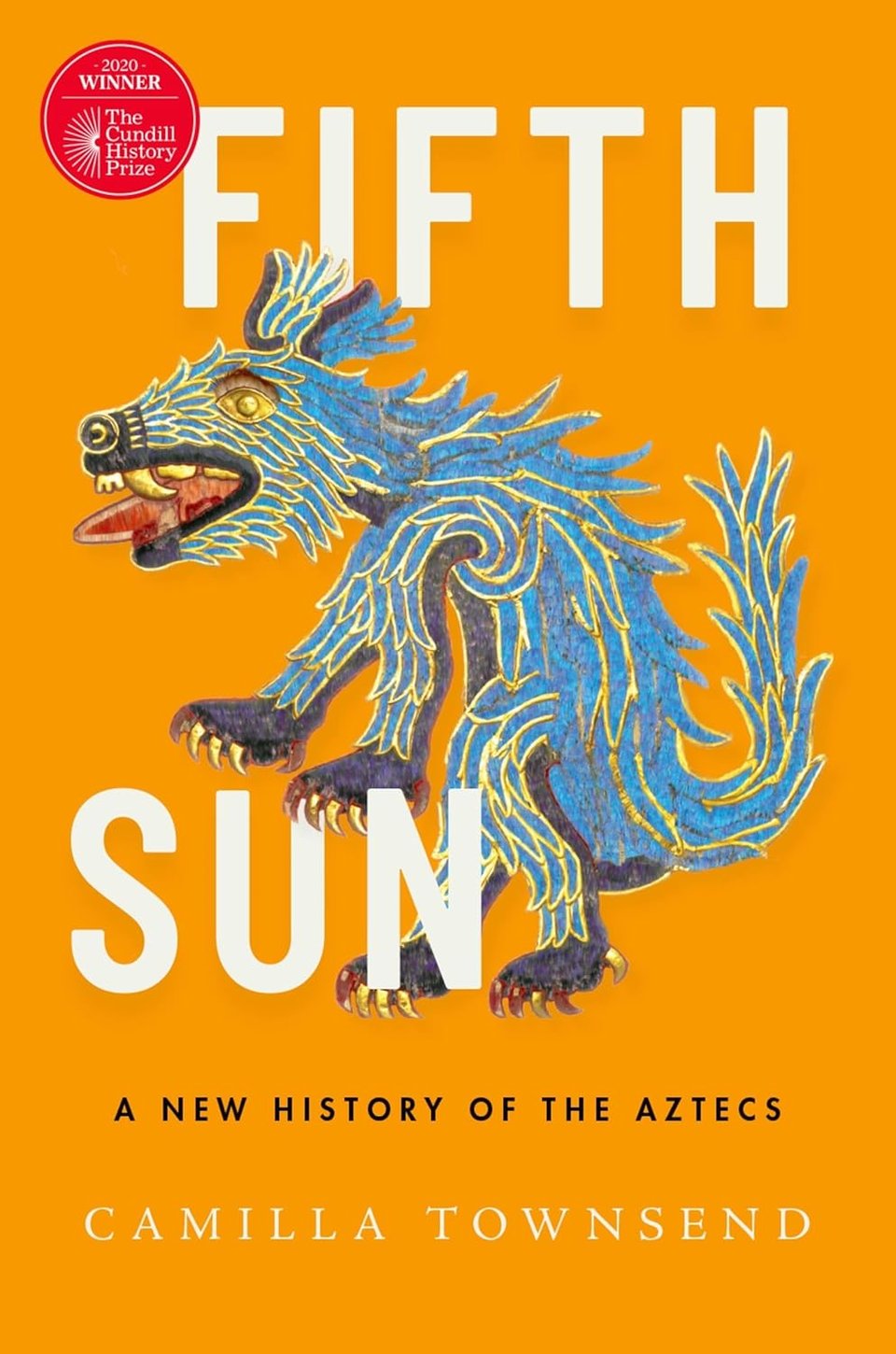

My reading list in the weeks leading up to the Mexico City trip included Camilla Townsend’s The Fifth Sun, a recent history of the Aztecs recommended to me by friend-of-the-newsletter (and fellow Buttondowner) Lizzie Wade, whose new book, APOCALYPSE: How Catastrophe Transformed Our World and Can Forge New Futures is coincidentally out this week. (More on Apocalypse in a future issue, once I’ve had time to read it, but for now you can read a sneak peek here.)

The Fifth Sun is history of the Aztec people (a name they never gave to themselves) as told through their own writings. From the book’s description:

In November 1519, Hernando Cortés walked along a causeway leading to the capital of the Aztec kingdom and came face to face with Moctezuma. That story—and the story of what happened afterwards—has been told many times, but always following the narrative offered by the Spaniards. After all, we have been taught, it was the Europeans who held the pens. But the Native Americans were intrigued by the Roman alphabet and, unbeknownst to the newcomers, they used it to write detailed histories in their own language of Nahuatl. Until recently, these sources remained obscure, only partially translated, and rarely consulted by scholars. For the first time, in Fifth Sun, the history of the Aztecs is offered in all its complexity based solely on the texts written by the indigenous people themselves.

I found this idea irresistible, and the book more than lived up to it. The book depicts the life and history of the various tribes and political faction that made up “Aztec” civilization with deep sensitivity and curiosity, and Townsend goes out of her way to debunk or clarify the topics of human sacrifice (not as abundant as you might think) and the idea that Cortés was mistaken for the god Quetalcoatl by the emperor Moctezuma, as well as other myths. The descriptions of the complex city systems of Tenochtitlan (where Mexico City now stands), the floating farms known as chinampas, and the political factionalism that undid the civilization, along with foreign germs, really helped colour and clarify our trip. I also loved You Dreamed of Empires, Álvaro Enrigue’s novelistic treatment of the first encounter between Cortés and Moctezuma, which I instantly picked up after seeing it referred to as an “Aztec West Wing.” Both receive the highest Something Good recommendation.

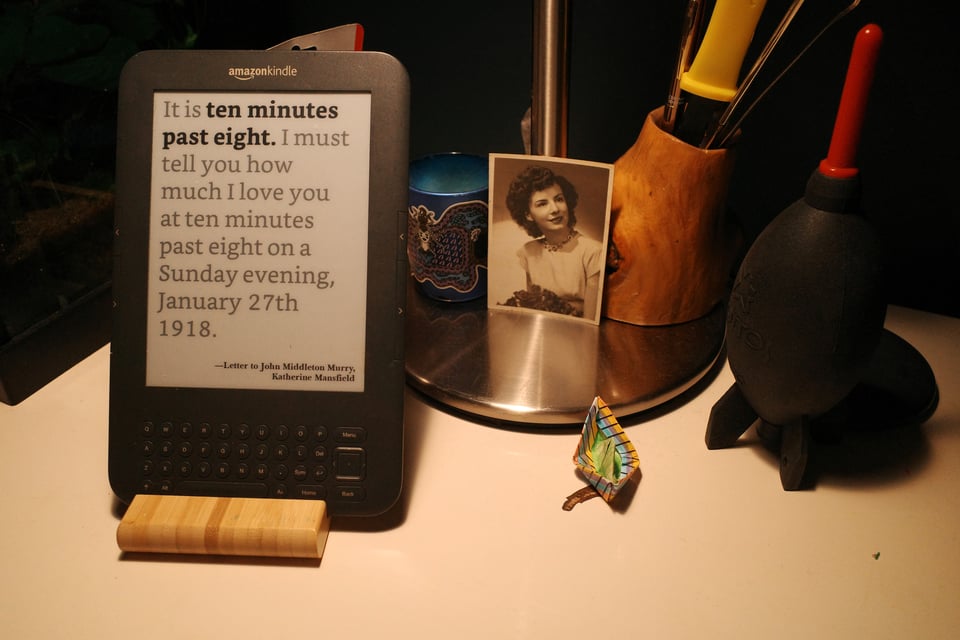

When I saw the Author Clock in an ad on Instagram, then later in real life at the MoMA store, I knew I had to have it. A handsomely encased e-ink screen which displayed a book quotation for every minute of the day, it was like a literary version of Christian Marclay’s The Clock—incidentally, Karen and my first date. What I did not want was to pay the price, which ranges between $200 and $350 USD before shipping, taxes, tariffs, etc.

So I was very excited to learn that somebody had figured out how to turn an old Kindle e-reader into one, for free. It’s not clear to me whether this project pre-dates the Author Clock, but a Dutch tinkerer named Jaap Meijers posted instructions for a “Literary Clock Made From E-Reader” to Instructables in 2018 or so, using as a resource a Marclay-inspired crowdsourced list of quotations organized by The Guardian in 2011.2 Some time later, a GitHub user named elegantalchemist posted their own instructions, as well as all of the necessary files and open-source projects, to their own project page, and one recent Saturday I decided fish out an old, battered and formerly beloved Kindle “Keyboard” (the kind that still had the good page-turn buttons!) from a box of toys and give it a new life.

This took me at least eight hours longer than I thought it would, but it actually worked, which I did not think it would. I will absolutely have to give credit to ChatGPT here, which I turned to after following the detailed instructions only returned a blank screen to me. Helping me with obscure computer stuff is absolutely a use case I approve of for generative A.I., especially when debugging something that it is absolutely impossible to Google.

I did notice with some interest how I interacted with the chat tool, though. As a heavily socialized human being who has been communicating with friends via the keyboard as far back as the BBS days, I have an instinctively casual and friendly tone with anybody I message with, human or not. The ChatGPT house style, almost abjectly cheerful and encouraging (to the point where it has really gotten out of hand) led to a very jaunty and pleasant conversation, even at those moments where you know the GPT is confidently returning a wrong answer and needs to be redirected with a firm hand. The next day, as I observed the clock working with satisfaction, I felt the impulse to go backstairs to the computer to tell the chatbot how well it had all worked out. That felt strange. I wonder if it will become a common feeling.

I want to take a minute to salute my brilliant colleagues at Compulsion Games. Our game South of Midnight, some five years in the making, was finally released last month, and the reviews have been incredibly positive and affirming. The New York Times gave it a coveted Critic’s Pick, and there have been too many great reviews to count, though I loved The Verge’s take on it, and IGN’s 8/10 review contains this excellent description of what sets it apart:

Southern gothic folklore hasn’t really been explored in games like this, and South of Midnight showcases how rich it is by bringing these tales to life in ways we rarely see. Mythical creatures embody the pain and suffering of townsfolk, melding broader urban myths with the struggles of specific characters throughout the story. A figure like Florida’s legendary alligator Two-Toed Tom shows up as a boss, while the shapeshifting Rougarou from Cajun tales takes a form I hadn’t heard of before – and Alabama’s Huggin’ Molly has on a fascinating reinterpretation. It’s the sort of amalgamation of folklore that’s wonderful to see as someone who is familiar with some of it, but done in a way that’s still inviting for the uninitiated.

South of Midnight acknowledges the region’s real history in subtle and effective ways as well, recognizing that remnants of slavery and the Reconstruction era persist in our modern world, and that trauma can carry across generations. Passing by abandoned houses along the bayou with eviction notices from greedy landgrabbers reminds you of the rough and unfair economic conditions many of these communities face. It’s woven into its main themes about the complicated dynamics of family—the best and worst parts that can come from blood relations. With her weaving powers, Hazel [the game’s protagonist] can peer into the past through visions recreated using the threads that make up The Grand Tapestry—the flow of all life and memory. You’ll see a mother risking life and limb to escape abuse and give their child a fighting chance; A man ashamed of his brother who takes drastic measures to separate himself, only to live with regret forever; A kid who called out to a mythical creature in desperation to escape his abusive father.

If you have a PC that can play games, or an Xbox, do check it out.

(Context: I’m Narrative Director at Compulsion, a position similar to Head Writer, and while I contributed in a small way to South of Midnight, this game wasn’t my project; and credit for its many narrative accomplishments belong to Lisa Hunter, Farah Brixi, Dani Dee Bell, Zaire Lanier, Kevin Snow, James Lewis, Maxime Archetto and many others.)

I’m pretty sure I found this newsletter’s #nojacketsrequired at the cabin of our friends Luc and Sheila. I have not read this book, nor any Alasdair Gray—should I? What you should do is send me your own dejacketed, denuded discoveries; it has been a long time since I ran a reader submission, and I’m beginning to wonder if you have all lost the faith. Write me at slutsky.mark@gmail.com.

The most unexpected Something Good shoutout award goes to this Masta Ace retrospective at The Quietus. More newsletters soon. As always, if you liked this, or dare I say, even loved it, please subscribe below or tell a friend.

I once bought a t-shirt from Uniqlo featuring a flyer Haring had designed for the legendary Paradise Garage disco on the back and felt kind of cool. That afternoon I went to a child’s birthday party and saw a three-year-old wearing the same shirt. ↩

Side note: interesting to see where most of these quotes come from. I guess it shouldn’t be surprising that so many of them were found in detective novels, where the exact time of day various and fatal events occur is usually of high importance. ↩

Add a comment: