Something Good #117: I Stepped Into a River

Why do we re-read?

“Do you see yon whirligig of water there?” Thin Amren pointed to an eddy below an alder root by the bridge. “He doesn't move. But water, she goes by. Then what's whirligig?”

“I dunno. It just—is,” said Joe.

“Then what is brook?” said Thin Amren.

“It's the brook.”

“And brook was here yesterday,” said Thin Amren. “And she'll be here tomorrow. Whirligig stays. Though he’s not the same water. Then what is yesterday? What today? What tomorrow? Whirligig, what is he? What is brook?”

“Oh, dry up,” said Joe.

—Alan Garner, Treacle Walker

You can never step into the same river twice, eat the same meal twice, play the same game twice, live the same life twice.

Why do I return to books, movies, songs, when there are so many new works left to explore? Despite an endless list of books and movies to get around to one day, I keep watching Ronin again, I always listen to the BBC audio adaptation of The Dark Is Rising when it starts to snow, I can’t tell you how many times I watched The Great Escape, slightly stoned, when it played on the CFCF-12 late night movie show. Don’t get me wrong, I consume the new all the time, but a re-read (like when I went through the Philip Pullman Books of Dust earlier this year) almost always feels like the actual version of the experience, to the 1.0 to the first, beta version attempt. Previews are over, and the real show is about to begin!

To clarify, I’m not talking about the idea of “comfort reading” or “comfort viewing”—art should jolt you awake, not lull you to sleep—and that complacent feeling is not what I come back for. A work of any depth should feel new and strange every time you revisit it, not like an old familiar friend, but… I guess, like someone from your past who you are only now realizing you never fully got closure with because you never really understood them.

But most of all, it should make you feel that way about yourself. Because, and this is as true for books and movies as it is for songs, what you’re going to encounter is a younger version of yourself wandering through those pages. When I read a book I haven’t looked at for 20 years, it brings back exactly where I was when I read it last, what I was eating, what was worrying me, all these little details that would have otherwise slipped away but added up to the lifeworld of the person I used to be. I can’t think of any other experience that has this specific, lasting (longer than a song or a madeleine) effect.

I think a lot about something Roger Ebert wrote about watching La Dolce Vita, first as a young hopeful, and then again in middle-age, when he had a radically different experience of the film:

In 1962, Marcello Mastroianni represented everything I dreamed of attaining. He was a newspaper columnist, he frolicked with beautiful women, he stayed up all night drinking and partying, he raced about the city witnessing colorful stories, he was a weary (but romantic) existential hero.

Ten years later, he represented what I had become, at least to the degree that Chicago offered the opportunities of Rome. Ten years after that, in 1982, he was what I had escaped from, after I stopped drinking too much and burning the candle at both ends. In 1992, he was a reckless young man with a weakness for romance. By 2002, he was the hero of a classic film, more than 40 years old, and I had to lecture audiences on the virtues of black and white. By then Mastroianni was dead.

When I first saw My Dinner With Andre I was a yearning teenager fascinated with the mysterious world of art just beyond my grasp, a world that seemed to live somewhere downtown, full of complicated people doing inscrutable things and having intimate relationships I could never quite understand. The lives of Wallace Shawn and Andre Gregory seemed impossibly glamourous, the experiences they described transcendent in their communion with a higher power of inspiration.

I returned to the movie in my 30s and realized it was about two very depressed men, each lost in their own way. Was this all I had aspired to? In some ways, I’d achieved it—money worries, minor career successes, a general sense of aimless dissatisfaction. The movie hadn’t changed, but I had.

I had a less disconcerting experience with one of my all-time favourite books. In my 20s, I was terrified to re-read Michael Ende’s The Neverending Story,1 a cherished book which I must have re-read dozens of times as a child, but thankfully, when I did go back, I found it richer and more profound than I had ever imagined. The younger version of myself, a lonely nerd who wanted to escape to Fantastica along with the book’s hero, Bastian Balthazar Bux, was still there, but now I understood a little better why the story had such a hold on me.

These experiences of revelation or disappointment aren’t limited to art. Why not cities, too? In the 1990s I backpacked through Prague, only recently post-Velvet-Revolution, and found the city, with one foot still in the Communist era, smokey workers’ bars, Soviet cigarettes, grey apartment blocks and Kafka-era tenements, so fascinating I prolonged my stay there for weeks and almost didn’t go home. More than a decade later I went back, spending a terrible week in an antiseptic youth hostel bickering with my girlfriend back home over Facebook Messenger, the city around me having transformed into what felt like just another generic Western European metropolis.

I had to get away. That week I escaped by bus to the medieval town of Český Krumlov, where I stayed in a little hobbit house by the river. I spent an idyllic day floating down the Vltava on an inner tube, occasionally stopping to buy a pint of beer or a grilled sausage from the demobilized military trucks that had been turned into food and drink stands on the river’s banks. I remember thinking, at the time, that this was the best day of my life. I’d stepped into a river of depression and hours later, I emerged from a different river, renewed. That night I ate bony pheasant at a tavern while watching rats scurry on the water’s edge, an image that’s always stayed with me fondly, despite it being pretty gross now that I type it out here.

After taking the bus back to Prague, I felt transformed again, and the city had, too—no longer the wondrous town of my teenage dreams, but a place where I could walk around, explore, eat potato croquettes, and chill the fuck out for a second.

When I was younger, everybody and their sister seemed to be reading Milan Kundera, a writer who at the time epitomized that sexy grown-up glamour that had fascinated all of us. And of course in Prague, in his home country, you saw him everywhere; every backpacker had their nose in The Unbearable Lightness of Being. This book I had read with, of course, zero lived experience, or comprehension of the erotic and political complexities he described.

All I really remember of it now, besides some naughty business with a bowler hat, is Kundera’s fixation with Nietzsche’s idea of “eternal return:” that we are fated, or doomed, to re-live our lives over and over again for eternity. This felt meaningless to me at the time, because if you were really to re-live your life precisely the same, with no memory of previous incarnations, it would feel exactly the same every time.

But what if life is like The Great Escape or My Dinner With Andre—what if it’s different every time? Is this my first run-through, or my millionth?

Next time I meet myself, I should ask.

I made a playlist of my favourite songs of 2025. This was a great year for music, especially if you like female-fronted electropop—guilty! Spotify and Tidal versions below. YouTube/Apple Music on request I guess?

A little while ago I had a plaque made for my desk that reads Nobody Reads Anything, a sort of writer’s memento mori, a grim check on my ego. Now this slogan is a talk at the Game Developers Conference 2026 (or “GDC Festival of Gaming,” as they’re calling it now), where I’ll be presenting with my very talented friends Kevin Snow and Laura Michet.

“Nobody Reads Anything: How Narrative Can Communicate So Other Disciplines Actually Listen” is a panel about how game writers and designers can express their ideas so they don’t languish in unread design documents and actually make it into production. If you’re into games and stories you might like it. And if you’re at GDC, please reach out and let me know, or better yet, come to the panel and say hi. GDC takes place in the second week or so of March, and the exact date of the panel should be announced soon.

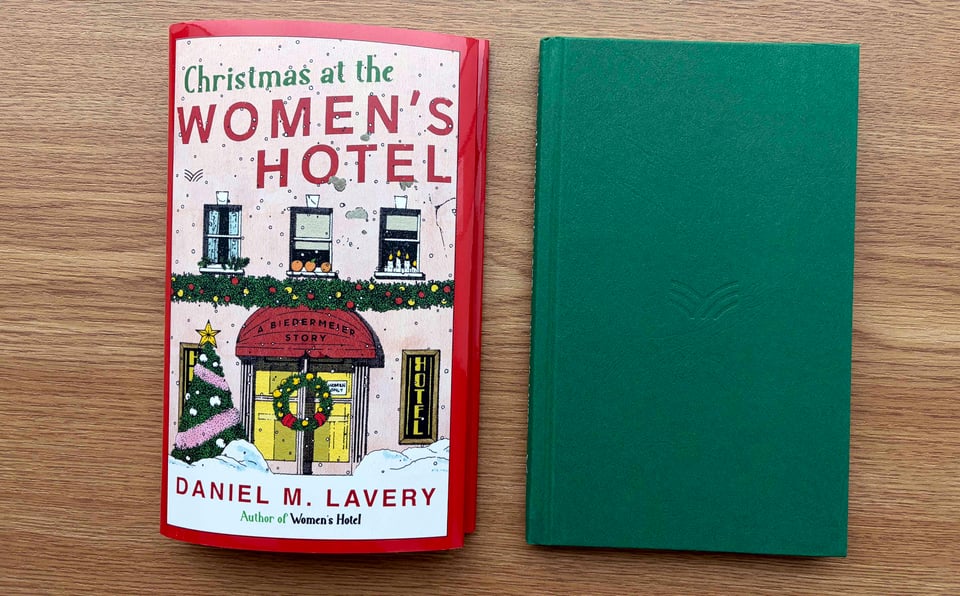

This week’s #nojacketsrequired is one of those cases where, yeah, the dust jacket is pretty great. But so is that lovely green! Yeah, I’ll probably keep it… but I’ll read it sans. Christmas at the Women’s Hotel is Daniel M. Lavery’s festive follow-up to last year’s Women’s Hotel, I book I really enjoyed. I’ll be sipping warm cider by my fake fireplace, wearing a cabled cardigan, while I read this one. As always—if there are any of you out there still committed to this project—send in your own finds to me at slutsky.mark@gmail.com.

This week’s featured epigraph is from The Empusium: A Health Resort Horror Story by Olga Tokarczuk (good book!):

Every day things happen in the world that can't be explained by any law of things we know. Every day they're mentioned and forgotten, and the same mystery that brought them takes them away, transforming their secret into oblivion. Such is the law by which things that can't be explained must be forgotten. The visible world goes on as usual in the broad daylight.

Otherness watches us from the shadows.

— Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet, translated by Richard Zenith

RIP to the legendary playwright and sometimes script doctor Tom Stoppard. I enjoyed this analysis of his draft of the script for Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade and was happy to see he was responsible for one of the funniest cutaways ever.

I finished The Rose Field, the new, and final book in Philip Pullman’s The Book of Dust trilogy, and I’m having a many feelings about it that I need to sort through. If you’ve also come to the end and want to share, please reach out to me so we don’t spoil it for the rest of them.

Congratulations to friend-of-the-newsletter Lizzie Wade, whose wonderful APOCALYPSE: How Catastrophe Transformed Our World and Can Forge New Futures has been named one of the best books of the year by the New Yorker, and rightly so. Check out our interview from earlier this year, and go read her newly rebooted email newsletter, The Antiquarian.

This has been, probably, the last Something Good of 2025. If you liked it, go ahead and tell a friend, or subscribe below:

Revisitation carries risks. A beloved old favourite might turn out to be terrible, or deeply problematic on some level. ↩

Add a comment: